The manhunt

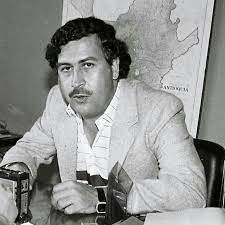

The manhunt was stepped up, but no new terms were given. It was now clear that Search Bloc, the American Delta Force, and special operations units were working together on the streets of Medellin and Bogota, where units searched every home and tried to find Escobar’s closest friends and family. When they searched the drug lord’s safe house in December 1992, they were very close to catching him. Pablo had only left it a few hours before. But things were getting better in other ways, too. Many of Escobar’s supporters and helpers started to turn their backs on a person they thought would eventually be caught, and staying loyal cost more and more. When Pablo’s brother-in-law was killed by Los Pepes, it was a clear sign that things were changing. Escobar was able to stay away from the police for almost a year and a half after his flight from La Catedral. The last thing that caught him was a surveillance operation that was able to follow his cell phone calls in the early winter of 1993. Because of this, Search Bloc and US agents found Escobar hiding out in another safe house in Los Olivos, a middle-class area of Medellin. They moved on December 2, 1993. Eight people broke down the door. Escobar and his bodyguard that day, Alvaro de Jesus Agudelo, also known as “El Limon,” ran out onto the roof of the building and tried to escape across the roofs of the houses next door. For sure, it’s not clear what came next. People started shooting at each other, and soon Pablo was lying dead on the roof, with bullets going through his leg, torso, and ear. Even though the bullet that went through his ear killed him, it is thought that Escobar fired the bullet himself because he had already decided some time ago that he would kill himself before being extradited to the United States. Roberto, Pablo’s brother and close friend, later said Pablo had always said he would shoot himself in the ear if he was pushed into a situation like this. No matter what the truth was, it didn’t change what happened. His death in Medellin on December 2, 1993, was just one day after his 44th birthday and about seventeen years after the start of the Medellin Cartel. He was known as “El Patron,” or “the Boss.” Escobar had made a strong image for himself as Robin Hood, even though he had caused a lot of violence. More than 25,000 people came to his funeral. As soon as Escobar died, the Cali Cartel quickly rose to become Colombia’s largest producer and trafficker of cocaine. The Norte del Valle Cartel, or North Valley Cartel, was a new group that came into being in Pablo’s last years in the Valle del Cauca region and gave it a lot of competition. In the 1990s, it became harder and harder for drugs to get from the Caribbean to Florida and the East Coast, so both groups looked for ways to get their drugs to Mexico. Mexico then became the new way to get into the United States. In the mid-1990s, the Cali Cartel was mostly broken up and pieces were scattered all over the place.

North coast cartel

New crime groups sprung up, like the North Coast Cartel, which was based in the northern city of Baranquilla and focused on supplying networks in eastern Europe while also bringing some of Pablo’s older supply lines up to the cities on the East Coast of the United States. All of these other groups have come and gone, taking their place with new ones that are determined to use more and more violent methods to get established. Today, Colombia is slowly getting back on its feet after the drug cartels and political conflicts that tore the country apart in the second half of the 20th century and made it possible for people like Escobar to do well. The Colombian government and the FARC rebels signed a historic ceasefire agreement in 2016. This meant that the country might no longer have to deal with paramilitary violence that had been going on for 50 years. Also, Medellin has done very well since Escobar died.

Medellin’s Story of Redemption: Escobar’s Dark History and the City’s Restoration

After the Medellin Cartel fell apart in the mid-1990s, crime rates in the city dropped quickly. Since then, the city has gotten a lot of investment and built up a lot of transportation infrastructure, which has made it a centre of business and industry in Colombia once again in the early 2000s. Thirty years ago, when Escobar was in charge, the city was known as the murder capital of the world. Now, it is known around the world for creating an environmentally friendly and innovative public transportation system. There are still other signs of Escobar’s influence. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, La Catedral was left empty for a long time. But in 2007, a group of Benedictine monks took it over and turned it into a religious site with a library and other features. The hippos, on the other hand, have grown in number and are still roaming around the Hacienda Napoles grounds. It was hard to figure out who Pablo Escobar was. His childhood was spent in the dirty city of Medellin, which grew from a small town to a city with more than a million people in the fifty years from the 1920s to the 1970s. He also became a drug dealer at a time when Colombia was going through a lot of political violence, which was really a civil war, and the country was also becoming the world’s centre for cocaine production. So, it’s likely that someone else would have become famous in the Colombian drug trade if Escobar hadn’t become the leader of the Medellin Cartel. This could have happened in Medellin, Cali, or somewhere else. One could also say that he did a lot to help the poor and the powerless, especially in his home town during a time when Colombia was in terrible poverty and many people felt like the government in Bogota had abandoned them. Pablo helped the poor by giving them money, making jobs, and improving Medellin’s infrastructure. People could even visit his zoo at Hacienda Napoles for free, and he made people feel better by giving so much money to the Atletico Nacional football team that they won the Copa Libertadores in 1989. This was the image of himself that Escobar tried to build up, like Robin Hood. The truth is much worse, though. Escobar killed a lot of people and brought violence and death to a level that had never been seen before in Colombia and Medellin in particular. There were a lot of problems in the country that weren’t his fault, but from the mid-1980s on, he became more determined to fight the Colombian government and rivals like the Cali Cartel. This is what made the country so dangerous that over 25,000 people were killed every year, with almost a third of those deaths happening in Medellin alone. Escobar may have been willing to give away a lot of his money, since the Cartel couldn’t have used most of it by the mid- to late-1980s. But he was also ready to kill dozens or even hundreds of innocent people at a time to get rid of his enemies, like he did with Avianca Flight 203 and the Department of Security bombings in November and December 1989. Once his bad influence was taken away in the mid-1990s, Medellin and Colombia slowly began to make progress towards becoming better places to live. So, even though Escobar might have said he was just “a good man who sells flowers,” the truth was very different.

Cart is empty

Cart is empty