How did Escobar grow to the position of drug ruler?

Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, Pablo’s business continued to grow without any problems. He was pretty unknown at this point, compared to when he became famous as the King of Cocaine or El Patron, also known as “the Boss.” He was in charge of the Medellin Cartel, which continued to grow quickly and bring more and more cocaine into the United States. They also smuggled large amounts into other countries, like Spain, which was like Florida for the American drug market: it let drugs into the country. The complicated ways the drugs were moved got even more complicated. For example, boats pulled small submarines full of powder. Soon, Escobar’s network was bringing several tonnes of cocaine into the United States and Europe illegally every week. This made the gang as much as $60 million a day, or $20 billion a year. By the early 1980s, the Cartel was buying coca paste from plantations in neighbouring countries like Peru and Bolivia. This meant that their operations had grown beyond Colombia. South America now has a whole industry based on the operation. It was getting so much money for the Cartel that it couldn’t spend it, and even laundering and hiding it was becoming very hard to do. A lot of it was cleaned through Panama. One common way was to buy gold and then melt it down into forms that other countries could use as clean money. Even so, these methods had their flaws. So, instead of spending the money, huge amounts of it were hidden in homes all over the country, where no one would ever guess they were there. Even stranger, the Cartel bought a mansion with a Jacuzzi that could be rolled up and down. Some tens of millions of dollars were hidden in a secret compartment under this. The house was then given to a poor Colombian family without telling them about the compartment. The only catch was that the family had to leave the house every so often when money was added to or taken out of the compartment. Some of this money is still being found today, which is not a surprise. In 2020, Pablo’s nephew Nicolás Escobar found $18 million hidden in the wall of one of Pablo’s old homes. It’s not the first time that huge amounts of money have been found by accident in some of Escobar and the Cartel’s old homes. The risk of getting caught kept going up as the profits kept going up. Extradition was one of the things Escobar and other members of the Cartel feared the most.

Escobar’s Reign of Terror: Battling Extradition and Terrorist Tactics

In September 1979, the government of Colombia and the government of US President Jimmy Carter signed an extradition treaty. This meant that drug smugglers from Colombia who brought large amounts of cocaine into the US could be sent to the US to be tried for their crimes there. When this treaty went into effect in March 1982, it put Escobar in great danger. If he were caught and sentenced in Colombia, the level of corruption in the country would either keep him from being found guilty or give him a very light sentence in prison. But if he were sent back to the US and found guilty there, he would almost certainly spend the rest of his life in a maximum security prison. In response to this threat, Escobar and some of his friends started a terrorist campaign in the early to mid-1980s that included kidnapping, killing, and bombing people in Colombian politics, law enforcement, and the courts to try to get them to back out of the extradition treaty. It didn’t work, though, and drug traffickers like Escobar lived in constant fear of being extradited in Colombia throughout the 1980s.

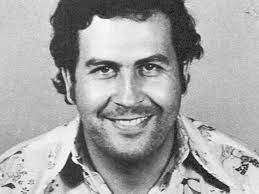

The Misleading Picture of a Colombian Hero

To avoid the risk of being extradited, Pablo tried to get support from people all over Colombia. A big part of Escobar’s mystery came from the idea that he was a Colombian Robin Hood. In the beginning, many people thought that Pablo and the Cartel’s actions didn’t really hurt regular Colombians. Any harm that their actions caused happened a long way away in the United States, which many Colombians saw as an imperial power that was attacking Latin America. To make his reputation even worse, Pablo gave away a lot of the huge amounts of money that were coming into the Cartel’s accounts every week. In some cases, he gave this to the people of Medellin as free cash. He also spent a lot of money on building projects in Medellin and across the country. He built football stadiums, parks and other public facilities. At one point, he even let people into the zoo at Hacienda Napoles for free. Improving the roads around Medellin was one of the most important investments. The city had grown very quickly in the 20th century and was now plagued by traffic jams. Pablo’s money helped fix some of these problems. Finally, Escobar would dress up as Santa Claus at Christmas and give expensive gifts to kids in poor areas. In this way, he bought the love of many people in Medellin and throughout Colombia. Even though people tried to make Pablo seem less bad, by the early 1980s he was known as the leader of the notorious Medellin Cartel and had a target on his back. So he came up with a new way to answer. He tried to get even more attention.

A Cascading Story of Political Ascendancy: Escobar, Bloodshed, and the Colombian Congress

He decided to run for office in Colombian politics in 1982 and was chosen by the Colombian Liberal Party. Pablo focused his campaigning on the extradition treaty between Colombia and the US, which was just going into effect. He said that the Colombian president, Julio Cesar Turbay, was giving up some of Colombia’s sovereignty by letting the US extradite Colombian citizens to its own country to be tried there. But Pablo also had people who didn’t like him during the campaign, and some of them were killed with bullets. During a debate in Medellin, a strong opponent said that Escobar was getting involved in politics for his own gain. Soon after, the man was arrested by elements of the Medellin police force that worked for the Cartel. After that, he was given to Escobar’s goons. A few days later, he was found dead on the streets of Medellin, his body full of bullet holes. So, Escobar was able to get elected to the Colombian Chamber of Representatives in March 1982 by using threats and his support for the people.

Escobar’s Political Strategy: Revealing the Conflict with Colombia’s Established Authorities

Pablo’s decision to get involved in Colombian politics was a controversial move. It helped hide his illegal activities and gave him a chance to question the extradition treaty from within parliament, but it also brought him a lot of attention that he didn’t need. What’s more, it made the conservative political establishment in Colombia start working to get rid of him. He used to be one of many drug dealers in the country, though he was the most successful. Now he was trying to bring down the country’s political establishment on purpose. It was especially important for Colombia’s new Conservative president, Belisario Betancur, to get rid of Escobar from politics. In order to do that, Betancur started a campaign against Pablo in the summer of 1983. One thing he did was make Rodrigo Lara Bonilla the minister of justice so that he could do a lot more to go after drug traffickers in Colombia, especially Pablo. At the same time, there was a media campaign against Escobar, and the newspaper El Espectador published a long article analysing Pablo’s arrest in 1976. This gave a lot of information about what had happened, how Escobar tried to hide the fact that he was arrested, and how he tried to avoid going to jail. Pablo was now being watched by the media in a way that he didn’t want because he was the face of illegal drug trafficking in Colombia. His first reaction to all the unwanted attention was the same as always. He thought about killing the editor of El Espectador and told people in the Cartel to try to buy as many copies of the newspaper as they could to cut down on its circulation. But within days, more stories came out that went beyond what was in El Espectador and showed how big the problem really was. But this would soon get bigger. In 1978, Carlos Lehder started buying land on Norman’s Cay, a Bahamian island, with the goal of turning it into a hub for cocaine trafficking between Colombia and the United States. Over the next few months, he used violence to scare local landowners into selling their land, even killing some of the residents. Lehder, who was unstable and paranoid, also pushed Jung out of the operation at this point. So, in just a few months, he had pretty much converted the island.

The Romantic Involvement with Virginia Vallejo

Some of these focused on his personal life and told how Pablo had started seeing a famous Colombian TV host named Virginia Vallejo. In recent months, Vallejo was the first reporter to have a one-on-one interview with Escobar. From that point on, their relationship grew. The trafficker had problems at home and in public because his wife Maria temporarily kicked him out of the family home and threatened to divorce him. This was fixed after a lot of pleading, but Pablo’s affair with Vallejo went on and off for another few years and didn’t end until 1987.

Escobar’s Resignation, Political Assassination, and the Increasing Conflict with the Colombian Government

Pablo was getting too much attention, so in late 1983, Gustavo Zuluaga, the superior judge of Medellin, decided to look into Pablo’s arrest in 1976 all over again. At the same time, Escobar’s American visa was revoked by the US embassy in Bogota, and Pablo’s special immunity as a member of the parliament was voted down by the Colombian Congress. Because of this, he decided to leave politics behind, knowing that his plan to get more protection from prosecution by getting involved in politics had backfired. And on January 20, 1984, he sent a letter giving up his seat in the Colombian Chamber of Representatives. In it, he said, “I will continue to fight against oligarchies and injustices, as well as against backroom dealings that show no regard for the people’s needs and especially against demagogues and dirty politicians who don’t care about the people’s suffering but are always on the lookout for ways to split up official power.” Three months after Pablo quit the Colombian parliament, on 30 April 1984, a Yamaha motorbike pulled up next to Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, who was in his car stuck in traffic in Bogota. Lara Bonilla was the justice minister and his job was to bring Escobar and Colombia’s other major drug traffickers to justice. Two men were on it. One was driving, but Ivan Dario Guisado, who was sitting in the back seat, quickly pulled out an Uzi submachine gun and started shooting at Bonilla’s car. The justice minister was shot several times and died right away. Soon after, Guisado was killed when Bonilla’s bodyguards returned fire. The driver, Byron Velasquez, had done what Escobar told him to do, which was like Pablo declaring war on the Colombian government. It was seen that way by the authorities, who then moved to fully carry out the treaty with the US on extradition. While this was going on, Pablo temporarily left Colombia with his family and lived in Panama, which is to the north. They then spent a short time in Nicaragua, which was in the middle of a full-blown civil war.

Cart is empty

Cart is empty